Part one of two articles by Katie Lloyd Thomas that explore the involvement of women in the building products industries and the architectural profession in the inter-war period. This is an abridged excerpt from the book Suffragette City: Women, Politics and the Built Environment edited by Elizabeth Darling and Nathan Robert Walker, published by Routledge in 2019.

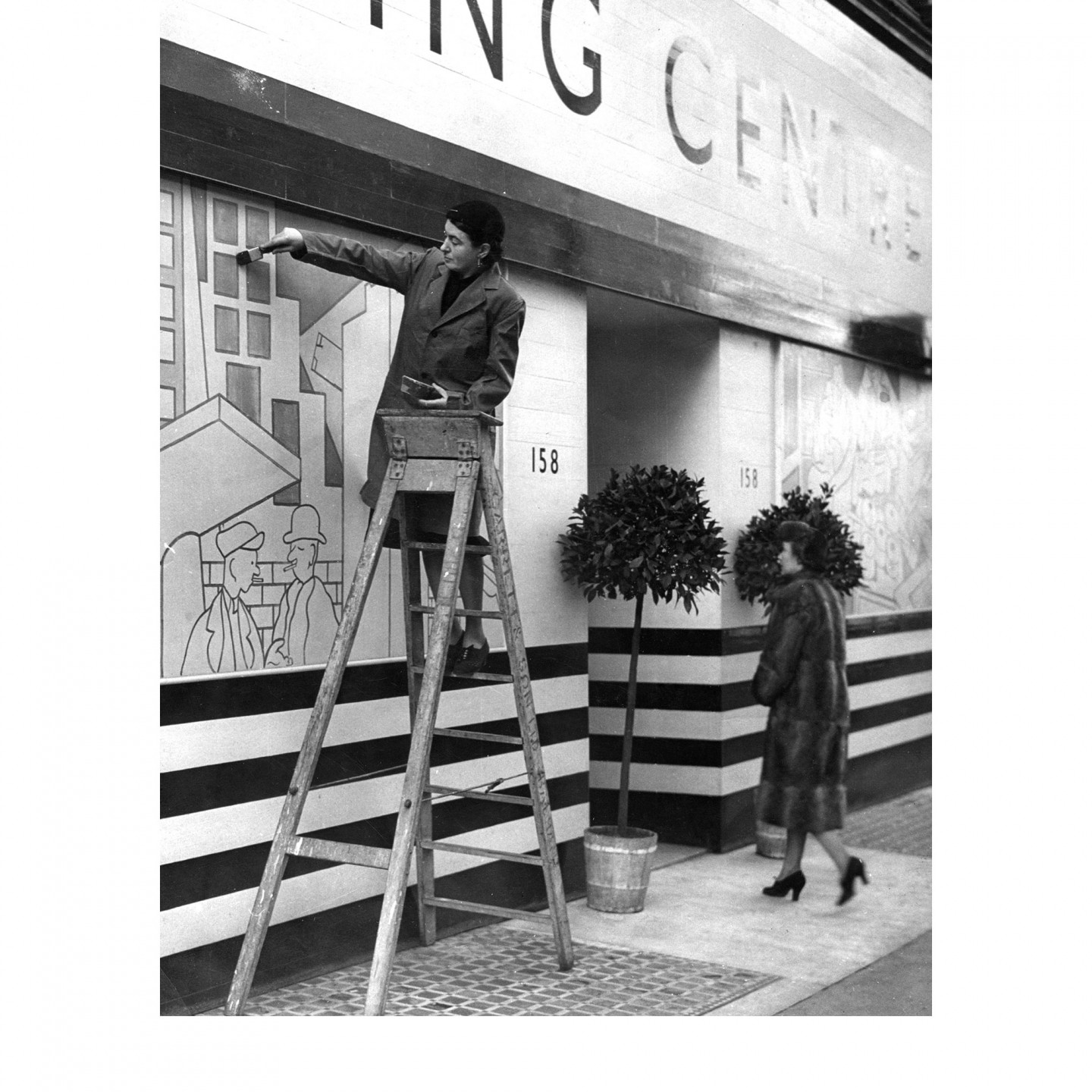

We thought Bond Street, the world’s most exclusive shopping centre, was a place to buy Rolls’ cars and diamond pendants; not to exhibit bricks and slates and patent floors. As we entered [the Building Centre], we noted an aristocratic lady looking at the cartoons of building activities in the window and then with a look of determination, she entered evidently intent on finding out what this strange interloper was doing in Bond Street. We do not think she was disappointed. There are more ideas in this free exhibition than in any shop in this famous thoroughfare.

The Builder (15 October 1932)

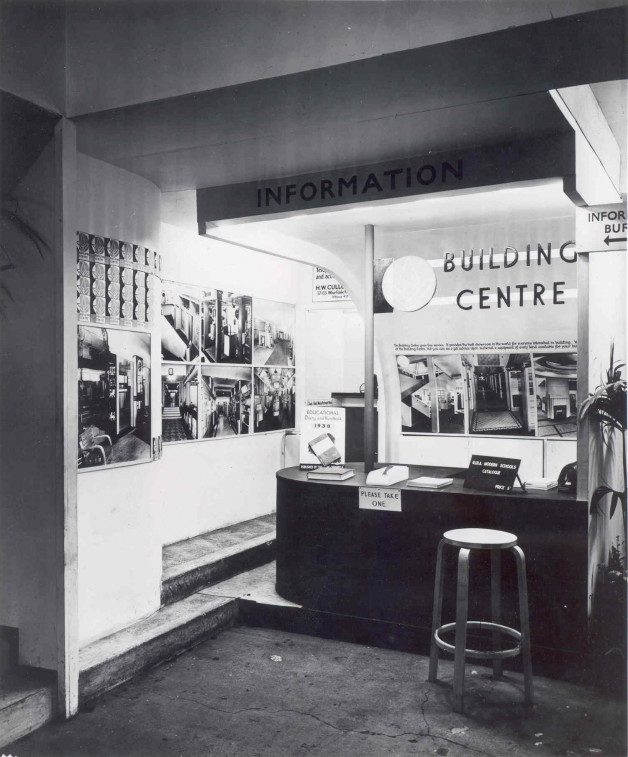

On 6 September 1932, a ‘strange interloper’ opened amidst the boutiques, auction houses and jewellers on New Bond Street at the heart of London’s fashionable West End shopping district. On display across the four floors of this elegant emporium were not the ‘Rolls’ cars and diamond pendants’ of its neighbouring stores, but the latest building products – from ‘bricks and slates and patent floors’ to boilers, plumbing and electrical equipment.

The Building Centre’s arrival caused a great stir in the national press, in trade journals and in women’s magazines. Its reviewers were particularly surprising on two fronts. First, as The Builder reported, many commentators were puzzled that such prosaic, technical products should be on display next to luxury stores such as Asprey, Louis Vuitton and Tiffany and Company. While building products bureaus could already be found in other major cities such as Berlin, New York and Oslo and indeed the Architect’s Technical Bureau, in nearby Bloomsbury, had added building materials and materials, to its comprehensive collection of manufacturers’ catalogues, the Building Centre was the first to introduce an elaborate display designed to appeal to and welcome members of the lay public. Second, there was considerable astonishment that so many of the Centre’s enthusiastic visitors were women. As the Edinburgh Evening News reported:

In less than a month, I hear, nearly 20,000 people have visited [the Building Centre], most of them being architects and builders, of course, but a surprising proportion being people with no professional interest in the exhibition. Very curiously, too, women have predominated amongst these ‘outsiders’.

Of course, Bond Street already attracted large numbers of female shoppers to its fashionable stores, and women too made up much of the audience at exhibitions such as the Daily Mail Ideal Home Show, with its hugely popular displays of domestic fixtures, fittings and furniture. One way to understand the Building Centre’s perplexing appeal to women would be to put it into the context of the other contemporary marketing drives that targeted female consumers and sought to sell them domestic goods.

There is, however, no evidence to suggest that the Centre’s founder Frank Yerbury, better known today as secretary of the Architectural Association (AA), then London’s leading school of architecture, had intended his new Centre to appeal to women in particular. The prospectus he produced to entice investors in the project set out its purposes as: ‘For the mutual benefit of architects and manufacturers of materials and equipment, and all those engaged in the building industry, and to stimulate public interest in building.’ As the numerous press reviews of its opening suggest, the Building Centre’s notable achievement was to take products that had hitherto been only of interest to those involved in the building industry and make them attractive and enticing to a public that included women. The technical products on display there – gutters, paints, roofing products – were altogether another order of goods to the refrigerators, curtains and washing machines that were so energetically promoted to women in the inter-war period.

The peculiar hybrid nature of the Building Centre – a blend of proprietary product information library and department store – and its popularity with women, represents more than simply an extension of the existing domestic appliances and furnishings market. The Centre was part of an enormous growth in the range of proprietary building products being manufactured and sold in the UK in the early twentieth century. Moreover, this was a process that saw architects recruited as brokers of these commodities. The architect took on a new role selecting one branded building product over another, a practice that was finally formalised in the writing of contractually binding building specifications in the 1930s. Thus, the architect became a conduit for guaranteed sales between the manufacturer and client/consumer, and the Building Centre acted as one of the mechanisms that facilitated this reconfigured set of relationships.

At the same time as it would provide information to experts in the industry, Yerbury intended the Building Centre as a place to which architects could bring their lay-clients to find out about the range of products on offer. Goods were not directly for sale but nevertheless the Centre needed to develop display techniques that could re-present them to appeal to a non-expert audience.

As in the electrical industry, which recruited vast numbers of women, not only to make goods in its factories, but also to promote and demonstrate the benefits of electrification and its labour-saving appliances to the female consumer, research suggests that women were also involved with the work of repositioning building products for a domestic market, albeit on a much smaller scale.

.jpg)