Eleanor Hill talks to Harriet Jennings about elevating local histories, the importance of the project’s intangible legacy during the pandemic, and the poignance of a selfie photobombed by a Longhorn cow.

The Wood Street Altarpiece illuminates your arrival to the eastern corner of Walthamstow, East London, with stories of the local community immortalised in vibrant vitreous enamel. The triptych celebrates the neighbourhood’s rich connections to the natural world, from the thriving network of community gardens to the ancient woodlands of Epping Forest.

It was created by designer Eleanor Hill whose proposal for a community engagement project won a competition by Waltham Forest Council to create a permanent public installation as part of the Making Places initiative. The resulting artwork is an uplifting celebration of the vitality and existing value of the area told through its people, at a time when it often feels as if a neighbourhood’s value is based on its potential worth in the eye of gentrification or a developer.

HJ: Could you tell us a bit about Wood Street in Walthamstow and how you got involved in the Making Places project?

EH: Making Places is an initiative by Waltham Forest Council where they asked residents to nominate sites that they want to be improved. They then launched an open call for artists and designers to submit design proposals for those sites.

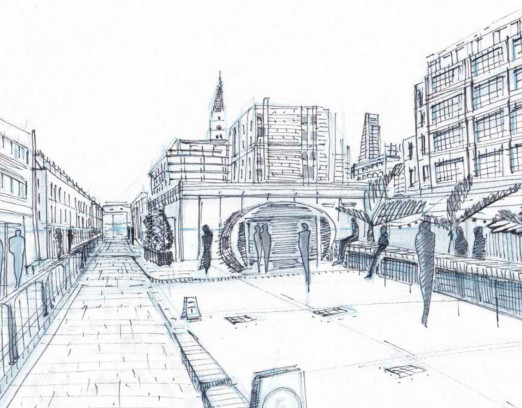

I was drawn to an underpass site in Wood Street. Wood Street has this incredible atmosphere – it’s bustling, it’s super diverse, it’s got this incredible high street packed with loads of independent businesses and just walking down the street you get a huge sense of there being a very active community. Wood Street is also a road leading directly to Epping Forest. This is London’s largest woodland – an ancient, ancient woodland – and it sits just on the edge of the city, a five minute walk from the train station.

The brief for the site was about improving the atmosphere of the dark and dreary unloved bridge that broke the high street off from the train station. The high street is predominantly on the right of the station and this bridge with a dingy lamp didn’t feel like an arrival point to what is a very bright and diverse community.

So I specifically entered the design competition for that site. But instead of a finished design I entered a design process that would involve lots of members in the community directly in the creation of the artwork. And that in itself is its own project – it has a whole online and offline life.

HJ: So you submitted a community engagement plan, rather than final aesthetic vision. How does that reflect your view on the role of civic artworks today?

EH: When I was getting to know the area I put forward the proposal to do a neighbourhood survey and uncover something very particular and unique about Wood Street by involving myself in several existing social networks and community groups that I had identified. My work is about that assertion that the citizen is the expert, the community is the expert, and they can tell me how to reflect the place they live in, and by doing that tell others. I think participation and engagement for me has been the most obvious way to contain a lot of different narratives and the expression of a community.

I think the role of public artworks today is not only to try and bring a joyful drama to a street or a place, but also to have a life outside of the physical piece of artwork. Whether that is the process behind it that involved a lot of people and in some way created a social resource, or social connections within the making of the artwork. Then you are getting more out of the project than you normally would. There’s the function of the public artwork creating this joyful drama and a visual impact, and then the second function and role is about the effect it has on people during and after the process.

HJ: What was your community engagement plan and where did it lead?

EH: Quite early on I discovered there was an incredible amount of community gardeners in the area. So I went gardening with a couple of the gardeners and did weeding and got stuck in just before the pandemic in 2020. I did an image based sharing exercise where I invited members of the community to submit an Instagram post – a photo and a caption – which reflected or celebrated their local green space. The project has an Instagram account @TheGardensofWoodStreet and a website www.gardensofwoodstreet.com where people were putting their entries in. So the project reflects what was going on informally and independently, and also what was going on collectively in the gardening groups.

HJ: And did those images inform the final artwork?

EH: Yes so all of the people in the artwork are real gardeners or local residents who submitted their portrait, as are all of the places and motifs, and animals and plant species. There were a lot of submissions about intimate relationships people had to plants in their garden. Because it was during the pandemic there were a lot of emotional entries about grief and plants being associated with loved ones or happier times. There were also practical entries like ‘here’s my tomato plant and here’s an incredible technique I use in my garden at home.’

A couple of people on that page had got in touch with each other and I could see from their social media posts that they were hanging out. So some people outside of the project started meeting up independently and making friends with one another. It has been amazing to see the connections that have happened – for example the gardens themselves have had a three fold amount of interest in their gardens and memberships. Because many people just didn’t know those resources were there.

So there’s the decorative artwork, which tells these stories in a formal way as an altarpiece, and then there’s this intangible social network happening, where people are making friends and learning new things and hearing about each other’s experience in a time when a lot of people were really lonely because of this huge national trauma.

HJ: You started the engagement before the pandemic struck, but it seems especially significant for a time like coronavirus – for connecting people when they are lonely, as you say, but also for celebrating green space that we now realise is so important for our health and quality of life. Why did you choose the form of the altarpiece to celebrate the green communities of Wood Street?

EH: Historically altarpieces sat within a period of human civilisation when there wasn’t popular literacy, and so altarpieces would act as physical story books. The messages presented in them were of huge social and collective significance. So, flipping that on its head I knew I wanted to present local or everyday stories that wouldn’t be necessarily attached to a spiritual or religious meaning, and not exclusive to my beliefs, but would be filled with figures from the area who were really contributing to their local environment in quite heroic ways.

It was really easy to find those figures. Wood Street South Gardening Club, depicted in the central panel, have been out in rain and sun planting bulbs, bedding trees, just in their own free time. They planted 5,000 spring bulbs in the last year. One local resident, Derrick Campbell, built all the street tree pits around the area. Memorialising those efforts felt really important because this is a fantastic example of community initiative and in a way elevating that in the context of formal, sacred, representation.

HJ: How did you structure the layers of imagery in the altarpiece and what are some of the stories shown in the panels?

EH: The three panels are divided into the three realms of local outdoor life – the left panel shows the forest, the central panel the public realm and streets, and on the right the home and private garden. The panels are framed by elements of the landscape and urban space – along the bottom is the high street that curves around to the Upper Walthamstow Road that takes you to the forest. One particular example of a story somebody shared with me for the forest panel was about a very specific flower that is on the brink of extension in the UK called the ‘Sickle Leaf Hare Ear’. It was recently discovered in Epping Forest and it is one of the only surviving colonies in the UK of this flower.

Similarly, the English Longhorn cow has been roaming in Epping Forest for thousands of years – and I didn’t know they were there, but someone sent in a photo of a cow photobombing a picnic. The cows are actually there to graze the acid grassland, and the grassland is really important to maintaining a unique ecosystem, and there are several species of butterfly that are contingent on acid grassland. So someone posting a selfie with a cow allows you to discover these stories, and I hope that now the artwork can in some way help people discover them.

I am currently finishing a booklet that will go to everyone that submitted photos and to the local library. It’s a pamphlet that has all of these stories in it. Obviously the artwork is open to interpretation, but there is a lot to unpack and I think the booklet will help people as a secondary layer to delve into stories.

HJ: In terms of making the structure, how did you pick the materials and who constructed it?

EH: The structure had to be suitable for the site – under the railway bridge – and there was only so much you could do to it because it’s a big piece of engineering that carries the overground. The aluminium metal work was produced by a fabricator called the White Wall Company who could take on the structure and the lighting. I drew the panels and they were screen-printed up in Birmingham because they had the largest kiln for vitreous enamel in the UK and could print in full size without splitting into sections.

It was an amazing opportunity for me as a recently graduated designer to have the support of an established fabricator who definitely made the process far less daunting. So much labour went into laying the colours as each is built up as an individual layer. The material of the enamel screen printing is actually colour itself, which has a thickness to it, unlike transfer prints, so it had to be designed in a way I knew could be screen printed.

You’re working with silhouettes and when you’re doing something quite spatial that’s nice because there are a lot of shadows and architectural motifs. I also think the process gives it a crafted finish in a way a normal altarpiece would have that handmade quality – there’s a lot of overlap and sometimes the edges are frayed a little bit. And that is just natural to the kiln and the process, the way it is fired and the way it is squeegeed. So you get those nice moments.

HJ: A distinctive use of colour runs through your work, including Terms of Endearment that you exhibited at the Building Centre in 2019. You’ve also spoken about using colour as a material – can you talk a bit about your approach to colour and its use in the altarpiece?

EH: A lot of thought goes into the role of colour and the accessibility of colour. I’ve been reading a lot recently about people with different colour perception, visual impairments and contrasts and the role different colours can play. And there is also a developing side of my work which is about the technical application of colour which is a craft.

And then there’s the social importance and impact of colour in our spaces and in our lives, and the role that colour can have in changing your mood and increasing the time you want to spend in a place. Colour can be a signifier of much more, it can indicate activity, pride and care. Giving the impression that something is important, valued and should be treated with attention and care, this impression is really important in building a sense of worth around a project.

HJ: Now that the altarpiece is installed and has been so well received, what are you looking forward to?

EH: Reflecting on the process and what I learnt about participation on a slightly larger scale. In terms of ambition I want to continue challenging and revising the role of participation within artwork and design. I think I'm most looking forward to continuing to discover more experimental forms of practice, and how participation techniques might create alternative models for social interaction and environmental stewardship at greater scales.

Find out more about the Making Places initiative and the artworks made for other sites in Walthamstow here.

See more of Eleanor’s work on her website here.

Download a digital copy of The Gardens of Wood Street booklet below.