Harriet Jennings spoke to project architect Ingrid Petit, of Feilden Fowles, and engineer Peter Laidler, Director of Structure Workshop, about materials and making the Fratry fully accessible for the first time in more than half a millennium.

Carlisle Cathedral has recently unveiled the biggest intervention to the historic precinct in 150 years. The Fratry hall, a historic priory refectory, is now open for the first time to allow public access to exhibition and events spaces, and a new café pavilion. Since its foundation in 1122, the cathedral has witnessed the UK’s turbulent history, giving the site a unique architectural layering whilst also earning it a reputation as Britain’s ‘unluckiest’ cathedral. Partially destroyed in the reformation and badly damaged during the civil war, the site has been used as a brewery, an arsenal, and had a stint as a Jacobite prison in 1745, before being restored as a place of worship. The cathedral now holds one of the UK’s finest library collections and is seeking to connect with the public and welcome the wider community to the cathedral through Feilden Fowles’ and Structure Workshop’s materially sensitive transformation of the Grade I listed 16th century Fratry.

Building Centre: Could you describe the aims of the new project’s brief, and the spaces designed to meet them?

Feilden Fowles: The project aimed to provide a new, fully accessible entrance to the Grade I listed Fratry building allowing both floors to be accessible to all for the first time in its history.

The new building now provides a multi-use reception / hospitality space to support the existing, refurbished hall and undercroft. Associated visitor and catering facilities are integrated within the building.

The cathedral was also very keen to ensure the building provided an element of outreach to the wider community, therefore making sure that the space was inclusive, inviting and welcoming to all was a key aspiration for the project.

BC: What was it like to work at such a historic site? Did it pose specific conservation challenges?

FF: It was a pleasure to work on such a historic site but also a pressure given the importance of its history. There were many conservation challenges from stylistic ones, including finding the right expression for the building to fit within the context of the existing fabric, to technical ones such as allowing for movement between the existing building and the new pavilion. The rigorous processes of achieving listed building consent, planning permission and HLF (Heritage Lottery Funding) grants ensured that our approach was thoroughly interrogated to deal with historic sensitivities. Furthermore, due to the sequence of historic events at the site, the unknown outcomes of the initial archaeological investigations also meant we had to be very patient and flexible to adapt to the findings.

BC: How did the history of the site inform your design?

FF: The project started with a careful analysis of the Fratry building fabric and cathedral precinct history in order to identify a suitable location for the new building and link with the existing. As a result, the pavilion is located to the north west of the Fratry, on the site of the former west range of the original Augustinian priory cloister, destroyed during the Reformation. Building on this site encouraged an expression of the former arcade, and whilst this now encloses the café pavilion, it pays homage to the rhythm of the cloister's pillars and arches.

BC: The Fratry is built in Dumfries red sandstone and installed by local stonemasons. Could you talk about your choice of material? How does it correspond to the fabric of the old building?

FF: A significant aspect of developing the technical design stages led us to visit several local quarries to identify an appropriate choice of sandstones including: St Bees, Cove Red, Locharbriggs and Lazonby. Whilst the cathedral and surrounding buildings have been built predominantly out of St Bees sandstone, the other three stones have also been used within the precinct for fabric repairs.

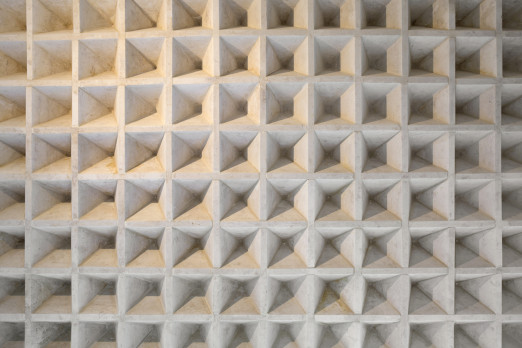

Ultimately, we selected the Locharbriggs sandstone for its technical properties but also for its colour which complements and blends with the existing surrounding buildings. Locharbriggs sandstone has a beautiful texture of dark veins depicting the ancient stone bedding planes from which it is extracted. This adds interest to the elevation of the pavilion whereby subtle lines accentuate the arches as they follow the radii of their sculpted curvature.

BC: What was the role of local craftsmen, such as the stonemasons, in the project?

FF: The stonemasons, Askins and Little, played a key role in helping us to finalise the details of the stonework. We had many meetings with them at the start of construction to discuss the drawings and organise the production of a 1:1 mock up sample.

It was invaluable to have their input and benefit from their knowledge on many things such as familiarity of the local stone, sizes of blocks, and traditional stone detailing.

BC: You have described your Homerton college project as ‘Arts and Crafts for the 21st century’. Was there a similar stylistic intention / combination of new and old technology here? Gothic for the 21st century…

FF: No, there wasn’t a similar stylistic intention at the start of the project. The language of the elevations was a result of extensive public consultations and testing in order to find the right expression to fit with the rest of the cathedral precinct.

We enjoyed the contrast between the high-tech innovation of using CNC-cut stones for the new elevations and the more traditional stone hand-carving for the existing building. We even found original pencil markings on the Smirke door stones when reversing the doorway which was a nice moment recalling how the former stonemasons had worked with this material before 2D and 3D digital modelling.

BC: Did you learn from the local artisans and the community during the process?

FF: The contractor and sub-contractor teams on the project were incredible and a lot was learnt from working together on this commission.

It has been fascinating to see how the opening of the building changed people’s perception of the cathedral within the city. Having the glazed café and courtyard seem to have made the cathedral grounds more approachable and many locals now enjoy stopping by the precinct and spending time in the new space.

Building Centre: Stone is the predominant material of the new pavilion. What were the specific demands of working the material?

Structure Workshop: Once the type of stone had been selected it was important to work within the limitations of the quarry to ensure that as far as possible the colour and texture was consistent and that the design accommodated practical constraints such as bed depths. Designing for durability was of paramount importance and the block arrangement was developed to ensure a robust arrangement with the correct orientation of the bedding planes and to avoid vulnerable details that might be susceptible to frost damage.

Of course, the form of the arches, their geometry and structural behaviour was carefully considered to ensure stability.

BC: How did you work with the stonemasons? Did you find yourself influenced by traditional techniques and knowledge of working with the material?

SW: It is important to look back at traditional techniques and to learn from what has been successful in the past. This is particularly true with stone which is the oldest of building materials. We were lucky in this project to have worked with masons Askins and Little and suppliers Cumbrian Stone on the project who are highly skilled and were willing to share their experience. It was fascinating and engaging to transpose their experience onto the proposals for a contemporary façade and this process generated much debate.

BC: You struck a delicate balance of the new project with the old, and a seamless transition between them. What were the challenges of working on such a historic site? Did some of them influence the project for the better?

SW: As design engineers we already had a lot of experience in materials, geometry and digital fabrication, in addition to traditional construction methods. But it was a real opportunity to fuse some of these disciplines, notably in the treatment of the stone arcade, and where the new building abuts the old at the mediaeval north wall of the Fratry. We worked through all the details in a creative process with Feilden Fowles, many of which were finalised during construction. There are several motifs from the cathedral and the Fratry that are referenced in the design and the structural arrangement.

BC: You ‘flipped’ the historic porch archway by Robert Smirke. Why? And what was involved?

SW: A series of previous alterations meant that the ornate stone entrance door by Smirke had been reversed by Street in the late 19th century to accommodate his porch, resulting in a set of steps between the door and the Fratry Hall. By (re)reversing the door and raising it by 400mm the new building combines to make the refectory hall and undercroft fully accessible for the first time since the construction of the Fratry in the 15th century.

The technical challenges to reverse the door and form a new opening into the undercroft were significant and required the wall to be propped before it could be dismantled. This was made more difficult by a Roman culvert which predates the mediaeval building and still runs directly under the Smirke door. The wall was monitored for movement throughout the works, and each stone labelled during reversal so that it could be put back in its rightful place. Only 1mm of movement was recorded when the temporary works were removed - testament to careful planning and the skill of the contractors on site.