A new exhibition ‘Stonehenge and Japan’, by English Heritage, has opened this month. On display are artefacts and site plans from ancient Japanese stone sites from the Jomon period, unpacking the relationship between social practices and the built environment. Like Stonehenge, the Jomon circles were constructed by Neolithic communities over thousands of years. Monuments like these two act as roots, used by communities to lay claim to special places. As the built environment acquires meaning over generations, the constructions themselves inherit a kind of ambiguous power. The material, stone, lends itself to this due to its longevity.

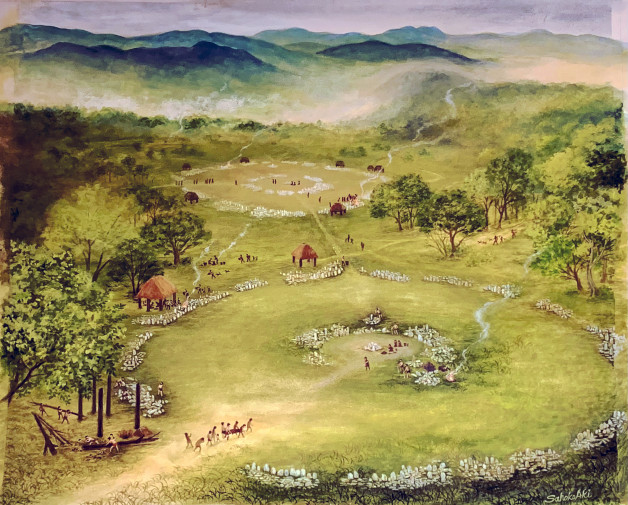

Britain became an island around 8,000 years ago due to rising sea levels. This new isolation meant communities were cut off from seasonal routes, hunting grounds, and social networks. The communities of people who remained on the island would continue to thrive as hunter-gatherers until around 6,000 BC, when farming communities from Europe began emigrating to Britain. This restored connection with the continent, and began to slowly reshape the way of life in the UK. Bones found close to Stonehenge indicate the presence of farmed beef and hunted venison at the same meal – biological analysis reveals both meats came from different places and were cooked in different ways, indicating a relationship between two groups of people with very different ways of life, implying the exchange of information and living practices. Around the same time, the Jomon period in Japan saw similar sites being constructed. The prehistoric Jomon stone circles are not megaliths like Stonehenge, but are comprised of thousands of smaller stones laid over generations. The most famous finds at the site are the Jomon clay pots, or ‘flame pots’. Used for cooking, these ornate vessels are indicators of what was prized by the community. In both Britain and Japan, food was a unifying and important cultural factor.

Remains of food show the ceremonial importance of the sites, places of feast and celebration. The Oyo stone circles in the Akita prefix are aligned on Midsummer and Midwinter solstices like Stonehenge, indicated by the presence of sundial stones at both. Perhaps surprisingly, we only realised the alignment of Stonehenge because of knowledge of Japanese stone sites. William Gowland was the engineer who excavated Stonehenge. As a young man in the 1850s he got a job running the Osaka mint - while looking for metal sources, he excavated over 400 burial mounds in the mountains of the region. He was a hobby archaeologist, and came up with the techniques to meticulously record everything excavated at a site as well as to photograph it. He was asked to excavate and restore Stonehenge after he returned to the UK in the early 20th century, and brought the techniques he developed in Japan to do so. Having spent years studying Jomon archaeological sites, he also brought cultural understandings of astrology with him, and was one of the first to posit that Stonehenge may have been positioned to align with the rising of the sun and moon.

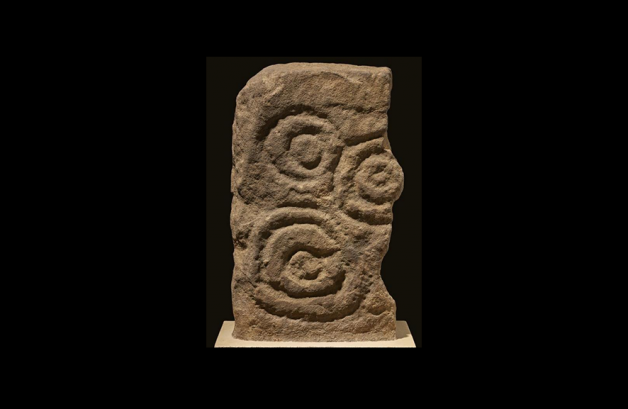

Both sites map the creation of a shared spiritual practice alongside everyday ways of living. Across the UK, a new symbolic language developed as communities created long-distance connections, and one material was essential to the propagation of this new visual culture; stone. Concentric designs became a feature carved into any available stone surface – tombs, houses (inside and out), seemingly random rocks, and artistic objects. This occurred simultaneously with the rush in monument building across the UK – the artistic consistency of this feat is remarkable. Due to the difficulty of working with stone as a material, large numbers of people had to collaborate efficiently to erect megaliths, and a symbolic dialogue emerged, likely influenced by practical material possibilities. The rock that was used to build megalithic sites was often not local, research has found the ‘bluestone’ Stonehenge is built out of came from quarries as far as Wales. More than 1000 people were required to transport each slab over 100 miles, and along the way a sense of community was forged alongside an intimate relationship to the land.

In Japan, similar designs proliferate – so similar in fact, it feels slightly unnerving. Spiral designs identical to the ones in Britain decorate the stones at the Oyo site, a seeming concentric obsession. At Sannai-Maruyama, the largest well-organised community of the same time as Stonehenge, Jadeite and Obsidian are found, brought from sites over 500 km away. Though the stones at these sites are not megaliths, they make up for stature in quantity. Laid over generations, thousands of stones continued to be interacted with, a constant reshaping of the built environment. These patterns, combining community and physicality, seem able to uphold a practice-led material spirituality. Their repetition as part of the visual language of those communities was surely part of what enabled the cohesive nature of their belief systems. The consistency of symbolism embedded within the architecture is a marker of what was an advanced social understanding of material.

In the UK, new settlers coming from the continent at the start of the Bronze age (known as Beaker people) were competing with Neolithic communities for control over the stone megaliths. Geological research shows that Stonehenge may have been vandalized or reworked by these new groups, and elsewhere stone circles were dismantled. We can see that as social relations fractured, or became less clear, so did material culture. The stones’ functions became more scattered, metal replaced stone as the ‘material of social and spiritual power’, and the shifting society present 3,000 years after the first communities settled in Stonehenge was unable to achieve the same level of consistency in their visual culture. In Japan, there are no signs of human conflict at the site as there are at Stonehenge, and it seems the new farming and metalworking communities migrating from mainland Japan had no interest in claiming these monuments as their own. The stone circles were left to nature. In a way, the lack of cultural reclaiming means their function remains more intact and true to the original intent than somewhere like Stonehenge, which has been preserved as a static monument and commercialised as a space. A stone circle called Oshoro in Hokkaido was found to still be in use by indigenous Ainu people, as stones from the site had shifted when recently surveyed, compared to a plan drawn up in the 1800s by a Scotsman - Monroe.

Material culture is a mirror for social relations, and by approaching history through an architectural lens, we may be able to glean insights into the mentality of a culture living in an area across a long span of time. By establishing a dialogue between culture and architecture a more complex understanding of both emerges. Instead of treating megaliths as mysteries, both exhibitions encourage us to understand them as manifestations of an incredible period of social transformation and see similarities across two cultures that we nowadays consider to be very different. The creation of these sites, and their later fall into disrepair, make them excellent markers for a time and culture-bound understanding of reality. Engaging with them makes us able to trace the waxing and waning of an evolving society and understand how material shapes social relations, and how those social relations in turn shape architecture.