It was in 1931 that Frank Yerbury, Secretary of the Architectural Association School of Architecture, started a small materials bureau in the school’s basement with the intention of demonstrating modern developments in building materials and products.

Soon the growing collection of materials demanded that the bureau be moved to larger premises. 158 New Bond Street became the Building Centre’s first home and where it opened its doors to the public on Wednesday 7 September 1932. Ideas, innovation and education were at the core of its mission with Yerbury’s ambition to connect the world of manufacturing with the practice of architecture.

“The basis of the Centre must always be an Exhibition of Materials and the policy should be that only such things are shown are of value to the building industry and the public…” – Frank Yerbury, 1937

Here, we celebrate the Building Centre’s unique story – from its impressive array of supporters such as Sir Edwin Lutyens to its progressive 1936 exhibition celebrating women architects – and provide a remarkable historical window into the world of architecture, and the materials and products that make up our built environment.

1930s

The Building Centre’s first decade of its inception saw an incredible array of exhibitions led by creative director Frank Yerbury. The ever first recorded exhibition at the Building Centre was Yerbury’s photography of Soviet architecture in 1932.

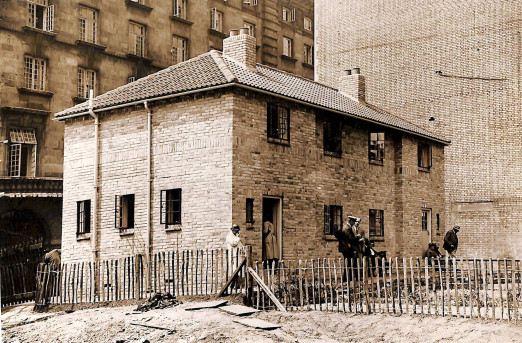

The Building Centre secured support from the Prince of Wales to launch the seminal low-cost housing exhibition of three-bedroom cottages. These semi-detached houses were built for less than £500 in London’s Aldwych. By the time the experimental houses had been demolished in September 1933, they had been visited by 20,000 people. Recommended article - The £500 house – we look at 90 years of housing at the Building Centre by Harriet Jennings

To this day, one of our favourite Building Centre exhibitions is the 1936 exhibition championing women architects. Unfortunately, the Press reports were a mixture of praise and condescension. We are also fascinated by the Inn Signs exhibition, a curious project which saw the Building Centre keep its doors open on the weekend due to popular demand. Read the exhibition guide from 1936.

Founded primarily with the intention of being a resource for “the building industry and public” the Building Centre established The Information Centre in 1935. With WWII about to break, the Centre presented an exhibition on air raid precautions in 1938. The centrepiece was a proverbial wartime Nissen Hut, a basic barrel vault of corrugate galvanized steel protected by sandbags and built by Nissen Buildings Ltd.

Recommended article - Women and the emergence of the Architectural Shopper – Part one by Katie Lloyd Thomas

1940s

In the first six months of 1940 an average of 500 people visited the Centre a week despite the outbreak of war. The 1940s ‘Railings for Scrap’ exhibition documented responses to the war effort in the built environment.

However, the Building Centre was not immune to the ravages of war. It lost its premises in New Bond Street due to an air raid in 1941. Soon after it relocated to 9 Conduit Street which was then damaged by shells.

The Post-war period saw the rationing of coal and in 1947 the electricity industry was nationalised. The 40s also came with revolutions in kitchen appliances such as microwaves and the fridge-freezer combo. In 1945, Queen Mary visited the Building Centre’s new all-electric kitchen display.

Recommended article - Railings for Scrap - Building Centre in the Blitz by Harriet Jennings

1950s

The 1950s saw the Centre host exhibitions of modern Swedish, Brazilian, Spanish and Yugoslav Architecture – many of them the first surveys of their kind in the UK.

In 1950 the lease was accepted for Building Centre to move into former Daimler Car showroom at 26 Store Street. Shortly before The Great Smog of London in 1952, the Centre fully embraces the move from coal to electricity. It lets its first floor to the British Electricity Authority and the Gas Council, replacing coal-burning appliances.

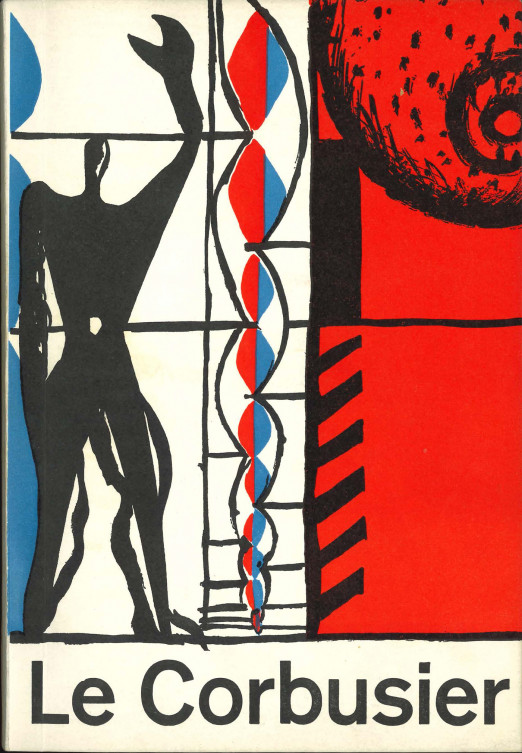

The grandest of the decade's exhibitions was the 1959 exhibition of Le Corbusier’s work which attracted over 37,000 visitors in just five weeks.The talk series included Jane Drew, Peter Smithson, Ernő Goldfinger and James Stirling as speakers. Read the 1957 exhibition guide here.

Recommended article - Le Corbusier exhibition at the Building Centre in 1959 by Mathilde Savary

1960s

By the 60s the Building Centre was gaining traction and expanding its reach as a resource for the built environment professionals and the general public. In 1961 the Building Centre had gone global with the International Congress of Building Centres – to which over 60 Centres belonged. That same year a brick library was set up showcasing an impressive 800 samples of brick from across England and Wales.

A hospital section was created to assist the NHS’s £500 million, 10-year programme of rebuilding and modernising hospitals in 1962. It was the centrepiece of state-of-the-art prefabricated operating theatres.

In 1964 The Building Centre published its manual for maintaining buildings after handover to clients – 3 decades before Construction (Design and Management) Regulations statutorily required buildings to comply with health and safety codes during and after construction.

W A Balmain, a contractor at Turner & Newall, attended a system building forum at the Building Centre in 1966, where he highlighted the lack of agreement of acceptable tolerances was “extremely urgent”. Two years later, the 1968 Ronan Point tower block in east London collapsed killing three people. Large gaps were later discovered in the joints that had failed to hold together the structural concrete panels.

1970s

Some consider the mark of the modern environmental movement to be ‘Earth Day’ – a large-scale environmental protest on 22 April 1970 in the US. Public agency to protect the environment grew and organisations such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, both founded in 1971, became leaders of the movement. That same year the Building Centre held film nights themed ‘pollution and conservation’ featuring; The River Must Live (1966), Environment in Balance (1970) and The Vanishing Coast (1965).

1980s

The last 90 years has seen incredible advances in how we store, receive, and share information. In order to stay relevant, the Building Centre has needed to constantly adapt in its mission to improve the flow of building information to professionals and the public.

In 1981 the Building Centre started exploring the new world of information technology, which in those days was served by primitive computer hardware and lacked the universal connectivity of the world wide web. One solution adopted by the Centre was Infodisc, a new standalone technology that combined colour images and text to assist in the comparison and specification of bricks.

1990s

During the 1990s, the Building Centre continued its expansion as a cultural and educational centre for the built environment. In 1991 it published a report looking 10 years ahead to the future. It concluded that “by the end of the century contractors will be receiving project data on disc or by network. Robotics will require greater prefabrication.”

In 1995 Dennis Crompton of the Archigram group designed an adaptable exhibition system of horizontal rails in ceiling and floor with vertical cables linking them. One of the first exhibitions was a flamboyant celebration of American cinemas called Ticket to Paradise.

At the same time, the centre played a key role in several major new government initiatives in building construction and town planning. Radical improvements to construction management and efficiency were proposed by the Latham report in 1994 and the Egan report in 1998. Then in 1999, Lord Rogers published his report Towards an Urban Renaissance. The Centre responded by hosting a lively symposium on how to attract people to live in urban neighbourhoods.

2000s

Marking 75 years of the Centre a major new exhibition ‘Materials of Invention’ takes place charting major innovations in modern architecture, from the Festival of Britain to the Millennium Dome. In 2006 the Building Centre turned its focus, as it has done many times since its 1933 three-bedroomed cottages competition, to affordable housing with the 60K House installation outside the building, the SixtyK Consortium’s winning entry in the Design for Manufacture competition, an industry challenge set by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister challenging the building industry to design quality housing at a build cost of £60,000.

By 2007, the proportion of the population in local authority housing stood at only 10%. That same year the Building Centre turned its attention from affordability to sustainability and exhibited No.1 Lower Carbon Drive – a full-scale model of a Victorian terraced house – in Trafalgar Square. The house showcased ways in which visitors could transform their home to reduce CO2 emissions. 'Lower Carbon Drive at Home' saw a scaled-down 'dolls house' version of the house come to Store Street.

2010s

As the Centre continued to welcome manufacturers and organisations to Store Street, 'We Made 2012' looked at the Olympic Games one year on, it remembered the challenges and accomplishments of staging a monumental event in our capital, and importantly, looked towards its legacy for Britain. It gave the people who made the Games the chance to show the result of their ingenuity and tell their story.

Today, 90 years on

Now in its 10th decade, the Building Centre's regular gallery exhibitions, online articles and talks continue to open up conversations about the important subjects of sustainability, retrofitting, climate change and the impact that the construction industry has had on our carbon footprint. It also continues to highlight new, innovative materials and techniques that will transform the way the built environment develops.

Over the last 90 years the mission of the Built Environment Trust, the charity which oversees the Centre, has grown and developed to inspire, connect and empower people to improve the quality of the built environment, recognising that it shapes lives and communities.

To celebrate our 90th Anniversary, and true to our mission to inspire, connect and empower, the Trust has brought to life a major initiative, ‘90for90’ which celebrates the last 90 years of the built environment throughout the UK. We have invited 90 leading figures from across Britain – from architects, engineers, planners and developers to actors, architectural historians, photographers, broadcasters, writers and artists – to select their favourite examples of our nation’s built environment.

We have encouraged each contributor to select a building or public space that has special significance for them. It may be a project they worked on; in a town, they have lived in, or perhaps somewhere that sparked their interest in their own career.

This is not just about buildings – the built environment is so much more than that. Our contributors were free to choose urban green spaces, sculpture parks, iconic structures, repurposed industrial buildings, public buildings, public houses, libraries, galleries, theatres, places of worship. The only criterion is that it must be something that resonated strongly with them.

.jpg)